Understanding Debasement Risk in Fiat Currencies

Debasement risk in fiat currencies is a critical concern for economists, policymakers, investors, and the general public. It refers to the reduction in the real value or purchasing power of money due to deliberate or inadvertent increases in the money supply. Understanding the mechanisms, history, and economic impacts of debasement is essential for navigating modern financial systems and safeguarding wealth. This article provides an in-depth exploration of debasement risk, with a particular focus on the U.S. Dollar (USD), and offers practical mitigation strategies for individuals and institutions.

Section 1: What Is Fiat Currency and Debasement?

Fiat Currency Basics

A fiat currency is government-issued money that is not backed by a physical commodity such as gold or silver but rather derives its value from the trust and authority of the issuing government. The term “fiat” means “let it be done” in Latin, reflecting the currency’s value by decree rather than intrinsic worth. Most modern economies, including the United States, operate on fiat currency systems.

Debasement: Historical and Modern Perspectives

Debasement originally referred to the practice of reducing the precious metal content in coins, thereby diminishing their value. In the fiat era, debasement occurs when the money supply increases significantly without a corresponding rise in economic output, leading to inflation and reduced purchasing power. Unlike physical debasement, fiat debasement is managed through monetary policy and central bank operations.

Section 2: Mechanisms of Debasement

How Increasing the Money Supply Causes Debasement

The primary mechanism of debasement in fiat systems is the expansion of the money supply. When central banks create new money—often to finance government spending, stabilize economies, or stimulate growth—more currency chases the same amount of goods and services. This dynamic is captured by the Quantity Theory of Money, expressed as MV = PQ:

· M: Money supply

· V: Velocity of money (how often a unit of currency circulates)

· P: Price level

· Q: Real output (goods and services produced)

If M increases significantly while V and Q remain stable, P (the price level) rises, resulting in inflation—a classic symptom of debasement.

Government Incentives and Debasement

Governments may be incentivized to debase currency to finance deficits, reduce the real burden of debt, or stimulate economic activity. However, excessive debasement can erode public trust, destabilize economies, and lead to runaway inflation.

Section 3: Historical and Recent Examples of Debasement

Ancient Rome

Roman emperors often debased silver coins by reducing their silver content and increasing base metals. Over centuries, the denarius lost most of its value, contributing to economic instability and public distrust.

Weimar Republic (Germany, 1921–1923)

In an attempt to pay war reparations and stimulate the economy, the Weimar government printed massive amounts of marks. Hyperinflation ensued: in 1923, prices doubled every few days, and the currency became practically worthless.

Zimbabwe (2000s)

Zimbabwe’s central bank dramatically increased the money supply to finance government spending. Hyperinflation peaked in 2008, with prices doubling every 24 hours and the Zimbabwean dollar ultimately abandoned.

The U.S. Dollar: Key Episodes

· Post-World War II (1945–1971): The USD was initially backed by gold (Bretton Woods System). In 1971, the U.S. suspended gold convertibility, fully embracing fiat currency. This shift enabled greater monetary flexibility but also increased debasement risk.

· 1970s Stagflation: Oil shocks and expansive monetary policy led to double-digit inflation. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose by over 110% from 1971 to 1980, significantly reducing USD purchasing power.

· Post-2008 Financial Crisis: The Federal Reserve implemented “quantitative easing,” expanding its balance sheet from $900 billion in 2008 to over $4.5 trillion by 2015. While inflation remained moderate, asset prices soared, and concerns about long-term debasement persisted.

· COVID-19 Response (2020–2022): In response to the pandemic, the U.S. government enacted stimulus packages totaling over $5 trillion. The money supply (M2) increased by more than 40% from February 2020 to June 2022. CPI inflation peaked at 9.1% year-over-year in June 2022, the highest since 1981.

· Current Trends: As of 2025, the U.S. faces ongoing debates about fiscal sustainability, with elevated deficits and public debt exceeding 120% of GDP. The risk of future debasement remains a topic of concern for policymakers and investors.

Section 4: Economic Impacts of Debasement

Reduction in Purchasing Power

Debasement erodes the real value of money, reducing what individuals and institutions can buy with their currency holdings. For example, $1 in 1971 is equivalent to about $7.60 in 2025 dollars, reflecting a cumulative inflation of approximately 660%.

Wealth Redistribution

Inflation resulting from debasement tends to redistribute wealth. Debtors benefit as the real value of their obligations declines, while savers and fixed-income earners lose purchasing power. Asset owners (e.g., real estate, equities) may see nominal gains, but these can be offset by inflation-adjusted losses.

Broader Economic Effects

Chronic debasement can undermine confidence in currency, distort investment decisions, and provoke capital flight. In extreme cases, it can trigger hyperinflation, social unrest, and economic collapse, as seen in historical examples.

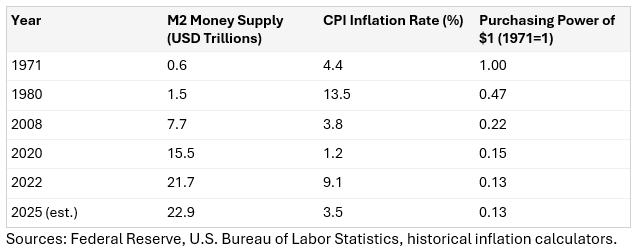

Quantitative Data: Inflation and Money Supply Trends

Section 5: Mitigations and Alternatives

Policy Safeguards

· Central Bank Independence: Ensuring central banks can operate free from political pressure helps maintain monetary discipline and reduce debasement risk.

· Inflation Targeting: Many central banks set explicit inflation targets (e.g., 2%) to anchor expectations and guide policy.

· Prudent Fiscal Policy: Limiting deficits and debt accumulation reduces the incentive to finance spending through debasement.

Investor Strategies

· Diversification: Holding a mix of assets (equities, real estate, commodities, inflation-protected securities) can hedge against debasement risk.

· Foreign Currency Exposure: Allocating some assets to stable foreign currencies can mitigate domestic debasement effects.

· Alternative Stores of Value: Gold, other precious metals, and select cryptocurrencies are sometimes used as hedges against fiat currency debasement.

Global Context

Debasement risk is not unique to the U.S.; many countries face similar challenges. However, the USD’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency provides some insulation, as global demand for dollars remains strong. Nonetheless, persistent debasement could threaten this position over time.

Conclusion

Debasement risk is an inherent feature of fiat currency systems, arising primarily from unchecked increases in the money supply. Historical and recent examples—including the U.S. experience—demonstrate the consequences of debasement: diminished purchasing power, wealth redistribution, and potential economic instability. Robust policy safeguards and prudent investment strategies are essential for mitigating these risks. As fiscal pressures and monetary experimentation continue, vigilance and discipline will be crucial to preserving currency value and economic stability in the future.

Disclaimer for Rocks, Stocks and Resources LLC

This newsletter and all associated content (the “Content”), including but not limited to articles, analyses, recommendations, and materials provided by Rocks, Stocks and Resources LLC (the “Company”), are provided solely for general informational and educational purposes. The Content is not, and should not be construed as, investment, financial, tax, legal, or professional advice; a recommendation to buy, sell, hold, or trade any securities, assets, commodities, or investments (including but not limited to mining stocks, precious metals, or energy resources); or an endorsement of any investment strategy.

The Company, its officers, directors, employees, affiliates, and contributors (collectively, the “Providers”) may have conflicts of interest, including but not limited to owning, trading, or holding positions in the securities or assets discussed in the Content. Providers may change such positions at any time without notice and have no obligation to update or disclose such changes to subscribers or users.

The Content does not consider your individual financial situation, investment objectives, risk tolerance, or circumstances. Investments in mining, resources, stocks, or related sectors are inherently high-risk, speculative, and volatile, with the potential for total or substantial loss of capital. Past performance is not indicative of future results, and no guarantees of profitability or avoidance of loss are made.

You must perform your own due diligence, independent research, and consult with qualified professionals (such as registered investment advisors, financial planners, tax experts, or attorneys) before making any investment or financial decisions. Reliance on the Content is at your sole risk and responsibility.

The Providers disclaim all liability and warranties, express or implied, for any losses, damages, claims, liabilities, expenses, or costs (including but not limited to direct, indirect, incidental, consequential, special, or punitive damages) arising from or related to the Content, even if advised of the possibility of such damages. This includes, without limitation, losses from market fluctuations, errors in the Content, or third-party actions.

The Content may contain errors, inaccuracies, omissions, biases, forward-looking statements, or outdated information. Forward-looking statements are inherently speculative and subject to numerous risks, uncertainties, and assumptions that could cause actual results to differ materially. Pay close attention to the date of any document, as circumstances, company information, market conditions, or regulations may change rapidly thereafter. The Providers make no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, reliability, suitability, or fitness for any purpose of the Content. The Content is not intended as, and does not constitute, a prospectus or offering document under securities laws.

This Disclaimer applies to all forms and methods of delivery, including but not limited to email newsletters, website content, social media posts, podcasts, videos, or any other media. By accessing, viewing, subscribing to, or using the Content, you acknowledge that you have read, understood, and agree to be bound by this Disclaimer. If you do not agree, you must immediately cease all use and unsubscribe. Use of the Content is restricted to individuals 18 years of age or older.

The Content may include links to or references to third-party websites, services, products, or information, which are provided for convenience only. The Providers do not endorse, warrant, or assume responsibility for any third-party content, privacy practices, or accuracy.

All Content is the intellectual property of the Company and protected by copyright laws. Reproduction, distribution, or use without express written permission is prohibited.

This Disclaimer shall be governed by the laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, without regard to conflict of law principles. Any disputes arising hereunder shall be resolved exclusively in the state or federal courts located in Suffolk County, Massachusetts. You agree to indemnify, defend, and hold harmless the Providers from any claims, losses, or damages arising from your use of the Content or violation of this Disclaimer. The Company is not a registered investment advisor, broker-dealer, or financial institution with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or any state securities authority, and nothing in the Content constitutes personalized financial advice, solicitation, or an offer to sell securities.

For questions about this Disclaimer, contact us at ryan@rocksstocksandresources.com michael@rocksstocksandresources.com